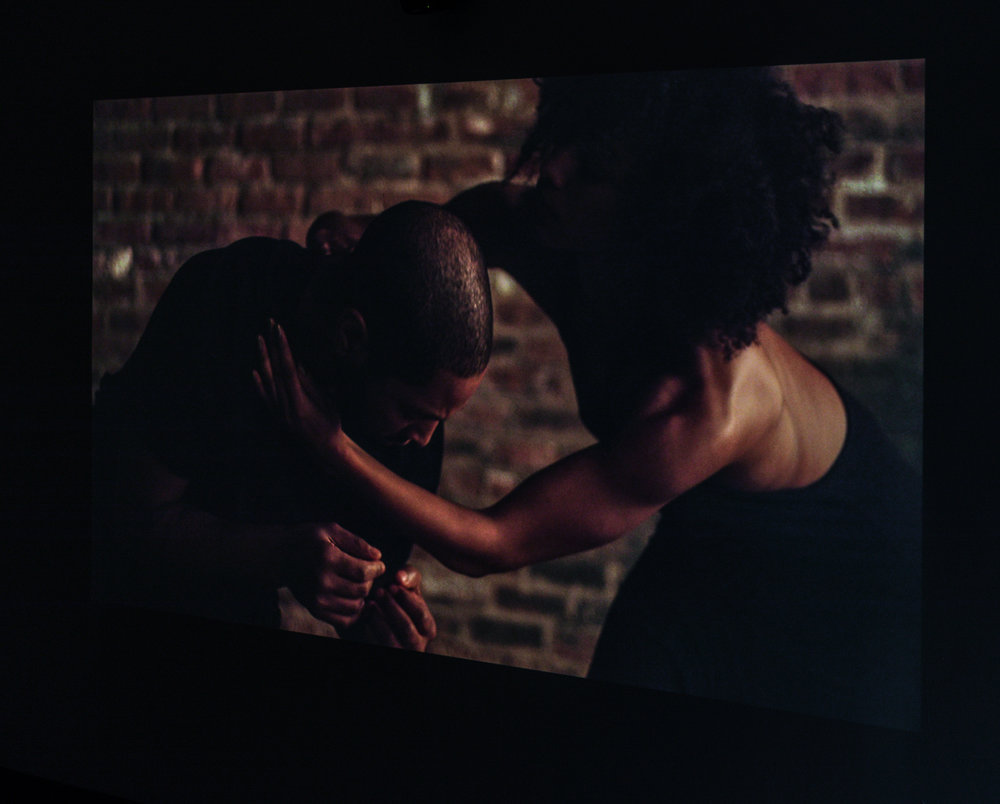

More Than Private was an exhibition of the photographic and video work of New York–based artist Carrie Schneider, curated by art historian Kaja Silverman. It was the first time Schneider’s work has been exhibited in Philadelphia, and her largest solo show to-date on the East Coast. Works on view spanned the last decade, and include Las Bebidas, Recession, Derelict Self, Reading Women, the Summer Drawings, three of Schneider’s videos, and five of the Dance Response videos, on which Schneider collaborated with choreographer/dancer Kyle Abraham. The show was on view from October 7 to December 13 at Slought.

More than Private opened on October 7, with a conversation between Schneider, Abraham, and Silverman about the Dance Response Project, and a riveting performance by Abraham. Silverman then conducted a second conversation with Schneider on November 30 that focused on Schneider's solo work and the notion of mutuality.

Use the slideshows below for a virtual tour of the exhibition at Slought.

FRONT GALLERY

Introductory Remarks

Although Schneider, like many of her peers, is a politically engaged artist, she differs from them in one striking way: she backs away from the abstract terms through which we conceptualize our “togetherness”—“masses,” “public,” “people,” and even adjectives like “plural,” and “collective.” She gravitates instead to objects, activities, experiences and conditions that are saturated with private meanings, and that might therefore be seen as a-political. “Solitude,” ”intimacy,” and “interiority” are her signature concerns. None of the works in this show, though, is private in the way property is supposed to be—that “belongs to,” or exists “for the use of one particular person or group of people.” There is also no work in this exhibition that is private in the way a person is supposed to be—complete, autonomous, and self-referential.

It is perhaps for this reason that we never feel that we are violating someone's privacy when we are looking at Schneider's work, even when the topic is something as "off limits" as the incest taboo. In fact, the opposite, is true: even at their most personal, the issues at the heart of Schneider's work are always"more than just private." This last concept comes from a 1925 letter from Rainer Maria Rilke, who had been living in a remote Swiss castle for six years, but had recently come to think of his writing as "more than just a private event." It is in a much earlier letter, though, that he offers his richest elaboration of this concept, and the one that—in its emphasis both on reading, and on the relational possibilities inherent in our childhood memories—is the most relevant to this show."One person or another would read what especially struck home to him in [the inexhaustible pages of Swann's Way]," Rilke writes, "and would hold it out in a specific way to the general opinion...and to many a one his own childhood would appear out of half-oblivion, and one would pass from tale to tale far into the summer night, but also far into the mutually rich true and alive."

Mutually rich. Mutually true. Mutually alive. It would be hard to imagine a better description of Carrie Schneider's work, or of the kind of political engagement that it promotes. (Kaja Silverman)

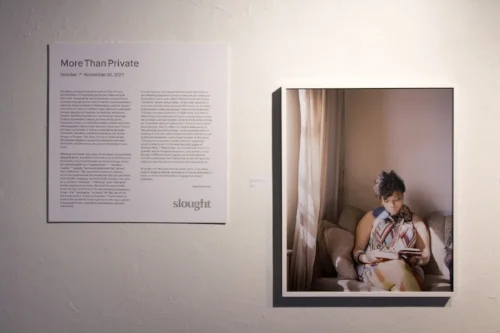

Reading Women

Like the story recounted by Rilke, Reading Women is about a group of readers, but instead of a handful of mostly French and presumably all-male luminaries, this group is made up of a hundred young women, and instead of gathering them together in the same room, to talk about a single book, Schneider gives each reader a room of her own, a photograph of her own, and a book of her own. Since she waited until each reader was engrossed in her book before photographing her, there is also a strange weave of two other kinds of interiority in the photographs: of the “inside” of a book, and the “inside” of a mind. And both formally and in many other ways, Reading Women recalls the similarly-engaged women in some of Vermeer’s interiors. What, we wonder after looking at a few photographs, makes this series more than private? What differentiates it from the paintings it so richly evokes?

This question, as we soon see, is built into the series, because Reading Women is not just about reading; it is itself a reading—a reading of women reading. It also invites us to read Schneider’s reading. And once we begin to do so, we realize that although there is only one woman in each photograph, there are always at least three women in the room: the reader, the author whose book she has chosen to read, and the photographer. And because Schneider is invisible, although present, it becomes increasingly evident that there is “more” to see than we are being shown. This holds the photographs open, in an almost cinematic way, makes each a call for another.

Finally, although each woman is reading a book of her own choosing, all of the books were written by older women. Each photograph is thus the building block for a new and desperately-needed kind of feminism: one based on trans-generational transmission. Together, the readers are also creating a new kind of canon—one shaped by the passions and predilections of a provisional assemblage, rather than the almost-always false consensus of a formal assembly.

Reading Women goes “inside” in order to transform what is “outside.” (Kaja Silverman)

Yvonne Rainer Reading

In this video, Yvonne Rainer delivers a lecture she gave for the independent study program at the Whitney Museum, which grapples with the kind of humor symptomatic of our time—morbid, peculiar, hysterical. From the outset, she sees how easily laughter can give way to anger, and asks how does one joke and laugh at all, given the gravely twisted deeds that pervade our headlines? Or is it that we must joke and laugh so that we don’t scream from our windows “I CAN’T TAKE THIS ANYMORE!’”?

Though she mainly addresses these questions to herself, Rainer doesn’t seek answers on her own. Instead, she looks to her audience for a redemptive politics of the joke. As the only one of Schneider’s “reading women” who reads aloud, Rainer reminds us that reading, like laughing and joke-telling, can and often has to be loud, emotive and social. When we read out loud, it becomes clear that our words are communal. Similarly, jokes only exist when they are shared. When we “get” a joke and burst into laughter with the others, we are forming a community; together we are letting our idiosyncrasies, our laughing bones (which are many and varied), triumph over the “serious” political clamors of our time, which tends more and more to yield nothing but anger, isolation and paralysis. (Tung Chau)

MAIN GALLERY

Summer Drawings

The soft, translucent forms of ferns, flora, fabric, hands, hair, and faces populate Schneider’s Summer Drawings, each a unique silver gelatin print made by directly exposing photographic paper in an eight-by-ten-inch view camera. Schneider’s prints, though made in-camera, are less photographs than “heliographs.” The word means “sun drawings” and was used by Nicéphore Niépce to describe the method he used to make View from the Window at Le Gras, the earliest known surviving photograph from nature, whose architecture emerged in the quiet darkness of a camera obscura over the course of an eight-hour exposure.

Similarly, Schneider’s description of these works as “drawings” recalls William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, published nearly twenty years after Niépce’s View from the Window was taken, as Schneider’s prints suggest a world that imprints upon, manipulates, projects, and envisions its own image: multilayered, abstract, intersecting, collaborative. In nearly all of these works, floating grids of windows intersect and eclipse recognizable forms, while their darkened panes—the effect of the reversal of light’s intensity by using photographic paper as a photographic “negative”—refuse entry, sequestering an inaccessible and private space that is not unlike the dark, unknowable space inside the camera itself, where these images were “drawn,” layer upon layer, exposure upon exposure. The resulting pictures are dense with figures and light, while objects, bodies, and nature frame one another: they delineate form, they cut silhouettes from light, they obscure from view, they transform themselves within the solitude of the camera (obscura). (Jessica Hough)

Dazzle Camouflage

Made during Schneider’s residency in Finland, Dazzle Camouflage alludes to two forms of protective disguise. The first concerns a widely used ship camouflage during WWI, which doesn’t conceal the look of the target, but rather its speed and range. The second is the tendency for animals, insects and plants to take on the appearance of their environment. While most believe the point of this is to scare off or escape the gaze of their predators, that is, to preserve oneself, Roger Caillois proposes a dramatically different reading: one that is aesthetic in nature. He argues that when animals, insects and plants try to mimic their surroundings, it is not because they want to survive; it is, rather, because they want to be part of the “picture” that these surroundings form. More than the urge to be safe, is a desire to break out of one’s skin and to be in communion with others (rocks, leaves, patterns, colors...) even if it means sacrificing the sense of “I.”

Here, the canoe pops and flashes. Like a wrapped gift, its zebra stripes are a travesty rather than a protection. In painterly terms, the boat stands out as the “figure” against the “ground” of the lake. Clearly, it doesn’t bother to hide itself. Yet, the body of the boat is immaterialized by the stripes so much that its “figure” all but dissolves. Masked by the pattern, its edges, joints, and hollows bleed into one another, erasing the entire anatomy. In the way it disappears unto itself, the canoe recalls the schizophrenic’s description of their whereabouts, which Caillois quotes in his essay, “I know where I am, but I do not feel as though I’m at the spot where I find myself.” This out-of-body feeling of not being able to see yourself where you are, even though others can see you just fine, is very much present in Dazzle. (Tung Chau)

Recession

In October 2008, the American stock market plummeted, dragging the country and much of the world into one of the worst economic crises in global history. Schneider’s Recession quietly probes the long aftermath of the collapse. A woman, freighted with brand-less but full shopping bags, leans precariously against a shop window, opaque with draped plastic, which reflects the light of the rainy nighttime street. The figure—still Schneider here—looks away in marked contrast to works like Las Bebidas or some of the photographs that comprise Derelict Self. The massively collective scale on which the 2008 economic recession was felt gives way to a multitude of specificities: each crisis particular and consequential, each of the 8.7 million jobs lost its own narrative nested within the web of a single global experience.

To recede: to move back or away; to withdraw; to grow less or smaller. The world of Recession is one of strong gravitational forces. And if suffering tends toward retreat into oneself, Schneider pulls the viewer in as well. The perspectival grid formed by the windows coalesces at a vanishing point provocatively out of frame, toward which the figure looks. All the while, she seems to dissolve into the storefront’s commodity-loving frame, and sink into the ground, signaling the stagnant moments after the fall. In the empty streets, lit by the red-light district glow of traffic lights and storefronts, Schneider gives us a picture of hardship that is much less the Farm Security Administration’s photographic record of American life in the 1930s than an eerie allegory, tinged with abstraction, anonymity, and the sense of isolation that pervades catastrophe. (Jessica Hough)

Las Bebidas

Las Bebidas is Schneider’s “remake” of Velázquez’s Las Meninas. She retains the dog, but democratizes the picture by eliminating the royal retinue, and changing the venue from a richly-appointed room in a Spanish palace to a Chicago dive bar, with cracked red vinyl seating, and cigarette butts on the floor. Like the other artists who have “remade” this painting—Edward Steichen, Pablo Picasso, Richard Hamilton and Yasumasa Morimura—Schneider puts herself inside it. Unlike most of them, though, she does not gravitate to the position of the author. There is nothing in Las Bebidas to identify her as the picture’s source—no brush, no palette, no canvas, and no camera. She is there, rather, as a beholder and a sitter.

Surprisingly, this in no way diminishes her agency; the picture seems to emanate from her—and by “her” I mean not only the look she directs at us, but also the arch of her high-heeled foot, and the odd ornament she forms with the extended fingers of her left hand. This also aligns her more closely with Velázquez, rather than less. Although he is the author of Las Meninas, that is not how he presents himself to us in the painting. He suspends the activity of painting so that he, too, can step forth as a beholder and a sitter.

There is also a deep affinity between Velázquez’s painting and Schneider’s photograph. Las Meninas was often characterized as a photograph in the nineteenth century, which is odd, because the kind of photograph it resembles—a large-format, two-sided picture—did not yet exist. Schneider is not the first artist to have remade Las Meninas as a large-format photograph. She is, however, the first one to have remade it as one that is also two-sided. The photographic image has always been two-sided, and although this two-sidedness has assumed many forms— negative/positive, shot/reverse shot, etc.—they have all modelled “reversibiliy.”

The kind of photograph that Las Meninas anticipates and that Las Bebidas actualizes is one in which this two-sidedness is articulated as a facing relationship between beholder and picture, and whose structure therefore rhymes with, and reminds us of, the ontological structure of our own Being. As Merleau-Ponty writes in The Visible and the Invisible, each of us is “a being of two leaves...from one side a thing among things and otherwise what sees them and touches them.” And because none of us can provide the hand with which our body is caressed, or the look through which it is acknowledged, we are as dependent upon others as this picture is on its beholder. Two is the smallest unit of Being. (Kaja Silverman)

Derelict Self

In Derelict Self, a series consisting of 10 chromogenic prints, Schneider and her look- alike brother re-enact their childhood relationship, which was intensely mimetic and intimate, by wearing similar clothing, echoing each other’s gestures, and eliminating the distance that an adult body is “supposed” to maintain from other bodies. The resulting tableaux, many of which were photographed from an oblique angle, feel awkward and constrained, and the figures in them strangely out-of-place. These “denaturalizing” strategies recall Brecht’s alienation-effect, but they are used in a very different way. In a Brechtian play, disjunctions of this kind are deliberately used to separate the actor from his role, the music from the narrative, etc., to expose the provisional nature of what are assumed to be eternal truths. Here, however, they occur involuntarily, and they dramatize the alienated relationship that Schneider and her brother have to their “own” pleasure.

At first this seems to be simply a particularly striking example of the contradictory relationship that we all have to our own pleasure; what Carrie and he brother most desire at an unconscious level is horrifying to them at a conscious level, since it precipitates guilt and super-egoic punishment. But the closer one attends to the specificity of this work, the more inadequate this account becomes. What makes the things that Schneider and her brother once found so pleasurable excruciating to re-enact as adults is of course the incest taboo. Lévi-Strauss describes this taboo

in the most impersonal of ways. “The fact of being a rule,” he writes, “completely independent of its modalities, is indeed the essence of the incest taboo. If nature leaves marriage to chance and the arbitrary, it is impossible for culture not to introduce some kind of order.” And although there is more room for desire in Lacan’s account, it is even chillier. The incest taboo subjects our desire to an “order of preference” that is “imperative for the group in its forms,” and which we are powerless to resist, because it is “unconscious in its structure.”

Although the tension in the two bodies in Schneider’s photographs demonstrates that she and her brother did indeed come to believe that their feelings for each other were guiltily incestuous, the imitative nature of her haircut, clothing, posture and gesture clearly show that identification was everybit as important as desire, and the oddness of the tableaux and the particularity of their activities suggest that her feelings for her brother were even more expansive and irresolute. The incest taboo didn’t just force her to repress her feelings for her brother; it standardized them. It “told” her what she “wanted,” and then it punished her for that desire. And since this “rule” operates automatically and without regard for what is personal, it must have broken the iridescent and multi-colored strands of our feelings for the first person who opened the world to us on the same impersonal rack.

There is one picture in this series, though, that stands apart from the rest: Bar. Where does the majestic repose of this photograph come from? Was the agency through which these bodies were reconciled with themselves and each other purely aesthetic? Or were the conflicts and dissonances that are so pronounced in the other photographs resolved through the addition of a third person? If it was through another person, what are we to make of this “threesome”? These are questions that we cannot answer without repeating the crime whose consequences this series lays bare: the crime of “nomination.” The kinship structure doesn’t promote kinship; it ends it. (Kaja Silverman)

Burning House

In 2010 and 2011, Schneider repeatedly traveled to northern Wisconsin, where each time she built a small wooden house and rowed it to an isolated island, set it afire, and filmed and photographed its immolation. Burning House is a meditation on the drama of the natural environment and on a particular place, with photographs documenting each season and time of day. The lateral expanse of the water is at odds with the intense, inward draw of the structure’s central window, out of which flames pour and smoke rolls upward, into the atmosphere. The tiny buildings stand like monuments: ephemeral but resilient; they seem never to collapse but to burn into the night and throughout the year.

But amidst Wisconsin’s painterly landscapes, with their jewel-toned skies and green tufts of changing trees, the square frames and triangle roofs of these solitary houses call to the larger context of the domestic sphere. As they burn, the structures evidence—“stand” for—Schneider’s elaborate, labor-intensive process, for which she performed a role traditional relegated to men: construction. And she burned it down, set it alight from the (feminized) inside out. But this destruction is not merely a protest, and nor, so much, was their construction. These are not the lonely homes of an evacuated American dream, nor private property with its attendant nuclear family set aflame, nor even the condensed icons of a larger, historically oppressive domestic landscape, but maquettes, glowing and quiet, whose fiery light fights with the darkness, echoes the sunlight, and whose destruction is fully an opening to the world and an unfolding unto the air. (Jessica Hough)

MEDIATHEQUE

*Photographs by Theo Mullen, Elliot Krasnopoler, and Andrew Uroskie.